Hi everyone!

There is a concept that is sometimes mentioned here and there. The Lagrange inversion theorem.

Let $$$x = f(y)$$$. We want to solve this equation for $$$y$$$. In other words, we want to find a function $$$g$$$ such that $$$y = g(x)$$$.

The Lagrange inversion theorem gives an explicit formula for the coefficients of $$$g(x)$$$ as a formal power series over $$$\mathbb K$$$:

In a special case $$$y = x \phi(y)$$$, it can also be formulated as

Prerequisites

Familiarity with the following:

It is required to have knowledge in the following:

- Polynomials, formal power series and generating functions;

- Basic notion of analytic functions (e.g. Taylor series);

- Basic concepts of graph theory (graphs, trees, etc);

- Basic concepts of set theory (describing graphs, trees, etc as sets, tuples, etc).

I mention the concept of fields, but you're not required to know them to understand the article. If you're not familiar with the notion of fields, assume that we're working in real numbers, that is, $$$\mathbb K = \mathbb R$$$.

It is recommended (but not required) to be familiar with combinatorial species, as they provide lots of intuition to how the equations on generating functions below are constructed.

Motivational examples

In my practice, most obvious use cases of the inversion theorem are related to the enumeration of trees.

Ordered trees

An ordered tree is a rooted tree in which an ordering of children is specified for each vertex.

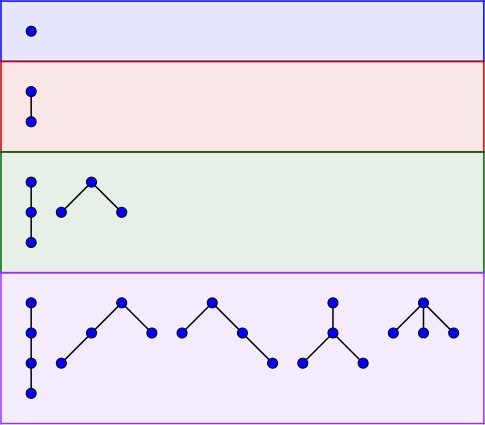

All ordered trees on $$$n \in \{1,2,3,4\}$$$ vertices.

The task is, given $$$k$$$, to find the number of ordered trees on $$$n$$$ vertices such that every vertex is either a leaf or has at least $$$k$$$ children.

Ordered tree can be described recursively in the following manner:

In other words, as a set-theoretic object, an ordered tree can be represented as a $$$(k+1)$$$-tuple, such that the first element is its root and the next $$$k$$$ elements are its subtrees, which are also objects of the ordered tree class.

We can enumerate ordered $$$n$$$-tuples of arbitrary objects from class $$$A$$$ as $$$A^n(x)$$$. And to enumerate them for every $$$n \geq k$$$, we would need to sum up the functions, obtaining the generating function for the ordered sets of ordered trees:

Let $$$T(x)$$$ be the generating function of ordered trees. Then it might be represented as

For $$$k = 1$$$, the solution is generated by

and for $$$k=2$$$, the solution is generated by

But as $$$k$$$ grows, the explicit formula for $$$T(x)$$$ gets more and more complicated (see the solution Wolfram found for $$$k=4$$$).

Alternate approach is to express $$$x=f(T)$$$. Then the Lagrange inversion theorem would still allow us to compute coefficients.

$$$k$$$-ary trees

Another task of interest is to enumerate the $$$k$$$-ary trees.

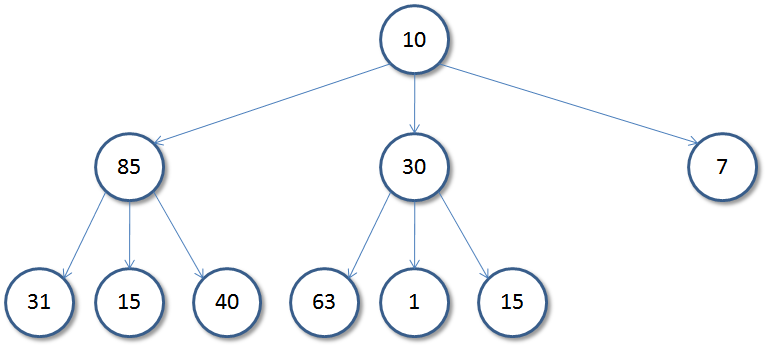

A ternary tree

A $$$k$$$-ary tree is a tree in which every vertex is either a leaf or has exactly $$$k$$$ ordered children.

The generating function for $$$k$$$-ary trees adheres to the identity $$$T(x) = x \cdot (1+T^k)$$$.

Labeled trees

Yet another task is to enumerate labeled rooted trees. While an ordered tree is represented as a pair of the root vertex and the list of subtrees, unordered tree may be represented as a pair of the root vertex and the set of subtrees. In other words, the generating function of the rooted trees adheres to the equation $$$T(x) = x \cdot e^{T(x)}$$$.

The later follows from the exponential formula which states that the generating function for the class of sets of $$$T$$$ is $$$e^{T(x)}$$$.

Note that this equation only works for labeled trees, and their exponential generating function:

where $$$a_k$$$ is the number of labeled trees.

Inversion theorem

Let $$$x = f(y)$$$. We want to solve this equation for $$$y$$$. In other words, we want to find a function $$$g$$$ such that $$$y = g(x)$$$.

This means that $$$x = f(g(x))$$$ and $$$y = g(f(y))$$$, so what we really want to find here is the functional inverse of $$$f$$$.

As it stands with generating functions, we're more interested in finding some expression for $$$g(x)$$$ as a formal power series, rather than closed elementary form (which may not exist). In doing so, we may use the Lagrange inversion theorem.

Formulation

Let $$$f,g$$$ be formal power series, such that $$$f(g(x)) = x$$$ and $$$f(0) = g(0) = 0$$$, then

where $$$[x^k] f(x)$$$ denotes the coefficient near $$$x^k$$$ in $$$f(x)$$$. In particular the $$$g(x)$$$ itself is found as

$$$x^{-n}$$$ in the formulas above expects negative power of $$$x$$$ and $$$f^{-k}$$$ expects the existence of the multiplicative inverse for arbitrary formal power series $$$f(x)$$$, which is problematic. To mitigate this, we expand the domain of functions we're working with to formal Laurent series.

Def. 1. The set of formal Laurent series $$$\mathbb K((x))$$$ over $$$\mathbb K$$$ is defined as

In other words, formal Laurent series is a formal power series, which is also allowed to have finitely many terms $$$x^k$$$ with $$$k < 0$$$.

When $$$\mathbb K$$$ is a field, $$$\mathbb K((x))$$$ also form up a field. In particular, it means that for a formal Laurent series $$$A(x) \neq 0$$$ there always is a multiplicative inverse $$$A^{-1}(x)$$$ such that $$$A(x) A^{-1}(x) = 1$$$.

Now that the formula is properly formulated, you may find the detailed proof below:

Note. Using the same reasoning, we can deduce it in even more general form for any analytic function $$$h(x)$$$:

In combinatorics

Quite often the equation that you deal with in combinatorics is formulated as $$$y = x \phi(y)$$$. Equivalently, it rewrites as

which boils down to $$$x = f(y)$$$ with $$$f(y) = \frac{y}{\phi(y)}$$$. Since

we have a formula

It is especially convenient due to the fact that we don't need to actually deal with Laurent series.

More general result for this case is known as the Lagrange–Bürmann formula:

for any analytic function $$$h(x)$$$.

Cracking up the examples

Ordered trees

The equation is

It means that $$$n [x^n] T(x) = [T^{n-1}] \phi^n(T)$$$, where $$$\phi(T) = 1+\frac{T^k}{1-T}$$$. To compute it, we use the binomial formula:

Note that $$$[T^a]T^b f(T) = [T^{a-b}] f(T)$$$. And, knowing the expansion

we may rewrite it as

Indeed, computing first few terms for different $$$k$$$ we see that

- $$$k=1$$$ yields Catalan numbers,

- $$$k=2$$$ yields Riordan numbers,

- $$$k=3$$$ yields the sequence A114997,

- $$$k=4$$$ yields the sequence A215341.

Further $$$k$$$ are seemingly not present on OEIS.

$$$k$$$-ary trees

The equation is $$$T = x \cdot (1 + T^k)$$$. So, for this case $$$\phi(T) = 1+T^k$$$ and we need to find

The expression on the right only has coefficient near $$$T^{n-1}$$$ when $$$k$$$ divides $$$n-1$$$, in which cases the number of trees is

for $$$n=kt+1$$$. Let's look on the generated sequences for different $$$k$$$:

- $$$k=1$$$ yields $$$\frac{1}{t+1} \binom{t+1}{t}=1$$$. Indeed, there is only one $$$1$$$-ary tree (bamboo) for each possible number of vertices;

- $$$k=2$$$ yields $$$\frac{1}{2t+1} \binom{2t+1}{t}$$$. This is actually the $$$t$$$-th Catalan number and another neat formula for them!

- $$$k=3$$$ yields the number of ternary trees (A001764);

- $$$k=4$$$ yields the number of quartic trees (A002293).

Labeled trees

The equation is $$$T = x e^T$$$. Let's find the coefficients with $$$\phi(T) = e^T$$$:

From this follows that

Note that we were specifically considering the exponential generating functions, thus the actual number of trees is $$$n! [x^n] T(x) = n^{n-1}$$$.

The function $$$T(x)$$$ can be expressed as $$$T(x) = -W(-x)$$$, where $$$W(x)$$$ is the Lambert W function (see e.g. here).