Hola Codeforces community! Sorry for the delay, we were solving some details of our national contest. We hope you enjoyed and learned a lot from this contest, we made it with much love. Our team worked day and night these last days to make sure you had a valuable experience :)). If you have any doubts about the editorial, please let us know in the comments, we are happy to help you. The editorial was prepared by jampm and me. Btw, best meme of the round.

2022A - Bus to Pénjamo

The key to maximizing happiness is to seat family members together as much as possible. If two members of the same family sit in the same row, both will be happy, and we only use two seats. However, if they are seated separately, only one person is happy, but two seats are still used. Therefore, we prioritize seating family pairs together first.

Once all possible pairs are seated, there may still be some family members left to seat. If a family has an odd number of members, one person will be left without a pair. Ideally, we want to seat this person alone in a row to make them happy. However, if there are no remaining rows to seat them alone, we’ll have to seat them with someone from another family. This means the other person might no longer be happy since they are no longer seated alone.

The easiest way to handle part 2 is to check the number of remaining rows and people. If the number of remaining rows is greater than or equal to the number of unpaired people, all unpaired people can sit alone and remain happy. Otherwise, some people will have to share a row, and their happiness will be affected. In that case, the number of happy people will be $$$2 \times$$$ remaining rows $$$-$$$ remaining people.

#include <bits/stdc++.h>

using namespace std;

int main() {

int t;

cin>>t;

while(t--)

{

int n,r;

cin>>n>>r;

vector<int>arr(n);

int leftalone=0;

int happy=0;

for(int k=0;k<n;k++)

{

cin>>arr[k];

happy+=(arr[k]/2)*2;

r-=arr[k]/2;

leftalone+=arr[k]%2;

}

if(leftalone>r)

happy+=r*2-leftalone;

else

happy+=leftalone;

cout<<happy<<endl;

}

}

- Write down key observations and mix them to solve the problem

2022B - Kar Salesman

Since no customer can buy more than one car from the same model, the minimum number of clients we need is determined by the model with the most cars. Therefore, we need at least:

clients, because even if a customer buys cars from other models, they cannot exceed this limit for any single model.

Each client can buy up to $$$x$$$ cars from different models. To distribute all the cars among the clients, we also need to consider the total number of cars. Thus, the minimum number of clients needed is at least:

This ensures that all cars can be distributed across the clients, respecting the limit of $$$x$$$ cars per customer.

The actual number of clients required is the maximum of the two values:

This gives us a lower bound for the number of clients required, satisfying both constraints (the maximum cars of a single model and the total number of cars).

Apply binary search on the answer.

To demonstrate that this is always sufficient, we can reason that the most efficient strategy is to reduce the car count for the models with the largest numbers first. By doing so, we maximize the benefit of allowing each client to buy up to $$$x$$$ cars from different models.

After distributing the cars, two possible outcomes will arise:

All models will have the same number of remaining cars, and this situation will be optimal when the total cars are evenly distributed (matching the $$$\displaystyle\left\lceil \frac{a_1 + a_2 + ... + a_n}{x}\right\rceil$$$ bound).

There will be still a quantity of models less than or equal to x remaining, which matches the case where the maximum number of cars from a single model $$$\max(a_1, a_2, ..., a_n)$$$ determines the bound.

Imagine a grid of size $$$w \times x$$$, where $$$w$$$ represents the minimum number of clients needed:

Now, place the cars in this grid by filling it column by column, from the first model to the $$$n$$$-th model. This method ensures that each client will buy cars from different models and no client exceeds the $$$x$$$ car limit. Since the total number of cars is less than or equal to the size of the grid, this configuration guarantees that all cars will be sold within $$$w$$$ clients.

#include <bits/stdc++.h>

using namespace std;

int main() {

int t;

cin>>t;

while(t--)

{

long long n,x;

cin>>n>>x;

vector<long long>arr(n);

long long sum=0;

long long maximo=0;

for(int k=0;k<n;k++)

{

cin>>arr[k];

maximo=max(maximo,arr[k]);

sum+=arr[k];

}

long long sec=(sum+x-1)/(long long)x;

cout<<max(maximo,sec)<<endl;

}

}

- If you don't know how to solve a problem, try to solve for small cases to find a pattern.

2022C - Gerrymandering

We will use dynamic programming to keep track of the maximum number of votes Álvaro can secure as we move from column to column (note that there are many ways to implement the DP, we will use the easiest to understand).

An important observation is that if you use a horizontal piece in one row, you also have to use it in the other to avoid leaving holes.

Let $$$dp[i][j]$$$ represent the maximum number of votes Álvaro can get considering up to the $$$i$$$-th column. The second dimension $$$j$$$ represents the current configuration of filled cells:

- $$$j = 0$$$: All cells up to the $$$i$$$-th column are completely filled (including $$$i$$$-th).

- $$$j = 1$$$: All cells up to the i-th column are completely filled (including $$$i$$$-th), and there’s one extra cell filled in the first row of the next column. $$$j = 2$$$: The $$$i$$$-th column is filled, and there’s one extra cell filled in the second row of the next column.

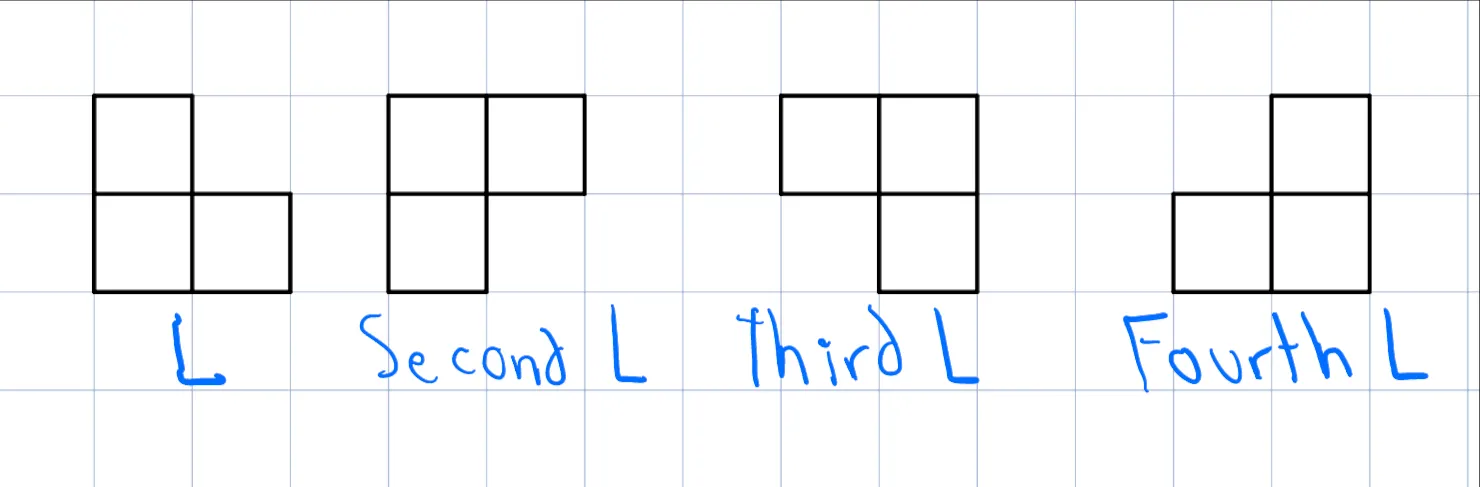

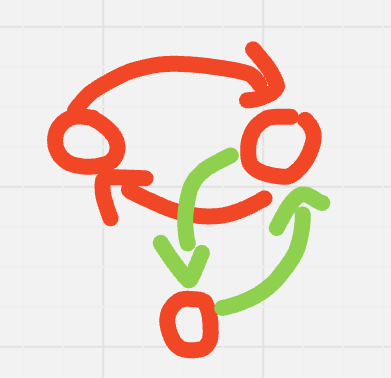

For simplicity, we will call "L", "second L", "third L", and "fourth L" respectively the next pieces:

- From $$$dp[k][0]$$$ (Both rows filled at column $$$k$$$):

- You can place a horizontal piece in both rows, leading to $$$dp[k+3][0]$$$.

- You can place a first L piece, leading to $$$dp[k+1][1]$$$.

- You can place an L piece, leading to $$$dp[k+1][2]$$$.

- From $$$dp[k][1]$$$ (One extra cell in the first row of the next column):

- You can place a horizontal piece in the first row occupying from $$$k+2$$$ to $$$k+4$$$ and also a horizontal piece in the second row from $$$k+1$$$ to $$$k+3$$$, leading to $$$dp[k+3][1]$$$.

- You can place a fourth L, leading to $$$dp[k+2][0]$$$.

- From $$$dp[k][2]$$$ (One extra cell in the second row of the next column):

- You can place a horizontal piece in the first row occupying from $$$k+1$$$ to $$$k+3$$$ and also a horizontal piece in the second row from $$$k+2$$$ to $$$k+4$$$, leading to $$$dp[k+3][2]$$$.

- You can place a third L, leading to $$$dp[k+2][0]$$$.

More formally for each DP state, the following transitions are possible:

From $$$dp[k][0]$$$:

From $$$dp[k][1]$$$:

From $$$dp[k][2]$$$:

To implement the DP solution, you only need to handle the transitions for states $$$dp[i][0]$$$ and $$$dp[i][1]$$$. For $$$dp[i][2]$$$, the transitions are the same as $$$dp[i][1]$$$, with the rows swapped.

#include <bits/stdc++.h>

using namespace std;

void solve()

{

int n;

cin>>n;

vector<string>cad(n);

vector<vector<int> >vot(2,vector<int>(n+8));

for(int k=0;k<2;k++)

{

cin>>cad[k];

for(int i=0;i<n;i++)

if(cad[k][i]=='A')

vot[k][i+1]=1;

}

vector<vector<int> >dp(n+9,vector<int>(3,-1));

dp[0][0]=0;

for(int k=0;k<=n-1;k++)

{

for(int i=0;i<3;i++)

{

if(dp[k][i]!=-1)

{

int vt=0,val=dp[k][i];

if(i==0)

{

// *

// *

vt=(vot[0][k+1]+vot[0][k+2]+vot[0][k+3])/2+(vot[1][k+1]+vot[1][k+2]+vot[1][k+3])/2;

dp[k+3][0]=max(vt+val,dp[k+3][0]);

vt=(vot[1][k+1]+vot[0][k+2]+vot[0][k+1])/2;

dp[k+1][1]=max(vt+val,dp[k+1][1]);

vt=(vot[1][k+1]+vot[1][k+2]+vot[0][k+1])/2;

dp[k+1][2]=max(vt+val,dp[k+1][2]);

}

if(i==1)

{

// **

// *

vt=(vot[0][k+2]+vot[0][k+3]+vot[0][k+4])/2+(vot[1][k+1]+vot[1][k+2]+vot[1][k+3])/2;

dp[k+3][1]=max(vt+val,dp[k+3][1]);

vt=(vot[1][k+1]+vot[1][k+2]+vot[0][k+2])/2;

dp[k+2][0]=max(vt+val,dp[k+2][0]);

}

if(i==2)

{

//*

//**

vt=(vot[1][k+2]+vot[1][k+3]+vot[1][k+4])/2+(vot[0][k+1]+vot[0][k+2]+vot[0][k+3])/2;

dp[k+3][2]=max(vt+val,dp[k+3][2]);

vt=(vot[0][k+1]+vot[0][k+2]+vot[1][k+2])/2;

dp[k+2][0]=max(vt+val,dp[k+2][0]);

}

}

}

}

cout<<dp[n][0]<<endl;

}

int main() {

int t;

cin>>t;

while(t--)

solve();

}

- Don't begin to implement until all the details are very clear, this will make your implementation much easier.

- Draw images to visualize easier everything.

2022D1 - Asesino (Easy Version)

Try to do casework for small $$$n$$$. It is also a good idea to simulate it. Think about this problem as a directed graph, where for each query there is a directed edge.

Observe that if you ask $$$u \mapsto v$$$ and $$$v \mapsto u$$$, both answers will match if and only if $$$u$$$ and $$$v$$$ are not the impostor. This can be easily shown by case work.

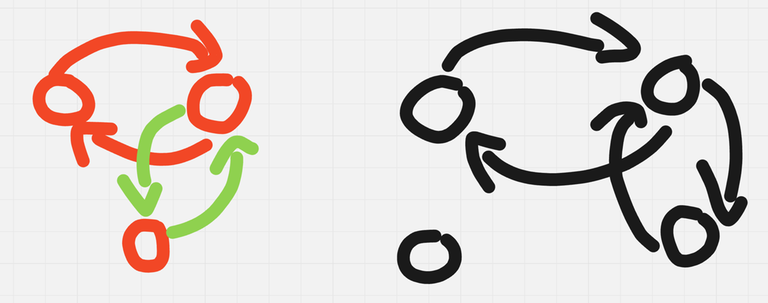

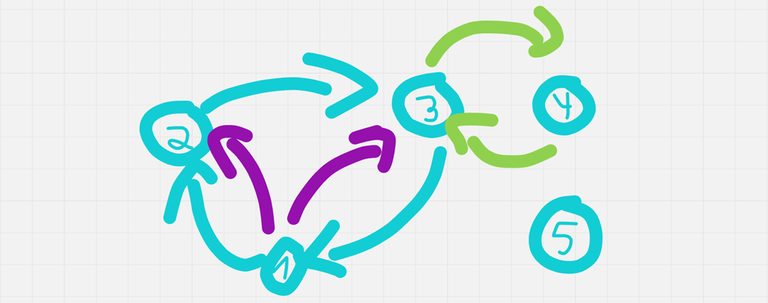

We can observe that $$$n = 3$$$ and $$$n = 4$$$ are solvable with $$$4$$$ queries. This strategies are illustrated in the image below:

There's many solutions that work. Given that 69 is big enough, we can use the previous observation of asking in pairs and reducing the problem recursively.

Combining hint 2 with our solutions for $$$n = 3$$$ and $$$n = 4$$$, we can come up with the following algorithm:

While $$$n > 4$$$,

- query $$$n \mapsto n - 1$$$ and $$$n - 1 \mapsto n$$$.

- If their answers don't match, one of them is the impostor. Query $$$n \mapsto n - 2$$$ and $$$n - 2 \mapsto n$$$.

- If their answers don't match, $$$n$$$ is the impostor.

- Otherwise, $$$n - 1$$$ is the impostor.

- If the answers match, do $$$n -= 2$$$.

- If their answers don't match, one of them is the impostor. Query $$$n \mapsto n - 2$$$ and $$$n - 2 \mapsto n$$$.

- query $$$n \mapsto n - 1$$$ and $$$n - 1 \mapsto n$$$.

If $$$n > 4$$$ doesn't hold and we haven't found the impostor, we either have the $$$n = 3$$$ case or the $$$n = 4$$$ case, and we can solve either of them in $$$4$$$ queries.

In the worst case, this algorithm uses $$$n + 1$$$ queries. I'm also aware of a solution with $$$n + 4$$$ queries, $$$n + 2$$$ queries, and one with $$$n + \lceil\log(n)\rceil$$$ queries. We only present this solution to shorten the length of the blog but feel free to ask about the others in the comments.

#include <bits/stdc++.h>

using namespace std;

bool query(int i, int j, int ans = 0) {

cout << "? " << i << " " << j << endl;

cin >> ans;

return ans;

}

int main() {

int tt;

for (cin >> tt; tt; --tt) {

int n, N; cin >> N; n = N;

array<int, 2> candidates = {-1, -1};

while (n > 4) {

if (query(n - 1, n) != query(n, n - 1)) {

candidates = {n - 1, n}; break;

} else n -= 2;

}

if (candidates[0] != -1) {

int not_candidate = (candidates[0] == N - 1) ? N - 2 : N;

if (query(candidates[0], not_candidate) != query(not_candidate, candidates[0])) {

cout << "! " << candidates[0] << endl;

} else cout << "! " << candidates[1] << endl;

} else {

if (n == 3) {

if (query(1, 2) == query(2, 1)) cout << "! 3\n";

else {

if (query(1, 3) == query(3, 1)) cout << "! 2\n";

else cout << "! 1\n";

}

} else {

if (query(1 , 2) != query(2, 1)) {

if (query(1, 3) == query(3, 1)) cout << "! 2\n";

else cout << "! 1\n";

} else {

if (query(1, 3) != query(3, 1)) cout << "! 3\n";

else cout << "! 4\n";

}

}

}

}

}

2022D2 - Asesino (Hard Version)

What is the minimal value anyway? Our solution to D1 used $$$n$$$ queries if $$$n$$$ is even and $$$n + 1$$$ queries when $$$n$$$ is odd. Is this the optimal strategy? Can we find a lower bound? Can we find the optimal strategy for small $$$n$$$?

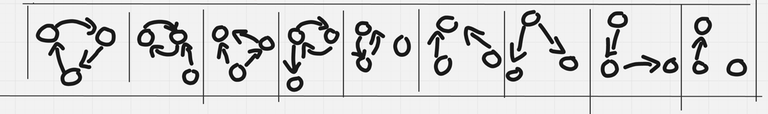

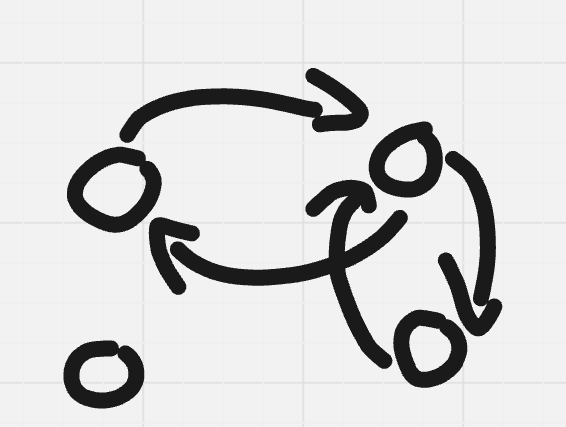

There's only $$$9$$$ possible unlabeled directed graphs with $$$3$$$ nodes and at most $$$3$$$ edges, you might as well draw them. They are illustrated in the image below for convenience though. Stare at them and convince yourself $$$4$$$ queries is the optimal for $$$n = 3$$$.

We would have to prove that $$$n - 1 < f(n)$$$ for all $$$n$$$ and $$$n < f(n)$$$ for $$$n$$$ odd. How could we structure a proof?

For $$$n - 1$$$ we have some control over the graph. We can show by pigeonhole principle that at least one of them has in-degree $$$0$$$, and at least one of them has out-degree $$$0$$$.

If those two nodes are different, call $$$A$$$ the node with in-degree $$$0$$$ and $$$B$$$ the node with out-degree $$$0$$$. Let the grader always reply yes to your queries.

- $$$A$$$ can be the impostor and everyone else Knaves.

- $$$B$$$ can be the impostor and everyone else Knights.

If those two nodes are the same, then the graph looks like a collection of cycles and one isolated node. The grader will always reply yes except for the last query where it replies no. Let the last query be to player $$$A$$$ about player $$$B$$$. The two assignments of roles are:

- $$$A$$$ is the impostor and everyone else in the cycle is a Knight.

- $$$B$$$ is the impostor and everyone else in the cycle is a Knave.

Note that the structure of our proof is very general and is very easy to simulate for small values of $$$n$$$ and small number of queries. Can we extend it to $$$n$$$ odd and $$$n$$$ queries? Try writing an exhaustive checker and run it for small values. According to our conjecture, $$$n = 5$$$ shouldn't solvable with $$$5$$$ queries. So we should find a set of answers that for any queries yields two valid assignments with different nodes as the impostor.

It doesn't exist! Which means $$$n = 5$$$ is solvable with $$$5$$$ queries. How? Also, observe that if we find a solution to $$$n = 5$$$ we can apply the same idea and recursively solve the problem in $$$n$$$ queries for all $$$n > 3$$$.

Consider the natural directed graph representation, adding a directed edge with weight $$$0$$$ between node $$$i$$$ and $$$j$$$ if the answer to the query ''? i j'' was yes, and a $$$1$$$ otherwise. We will also denote this query by $$$i \mapsto j$$$.

We will use a lemma, that generalizes the idea for D1.

Lemma:

The sum of weights of a cycle is odd if and only if the impostor is among us (among the cycle, I mean).

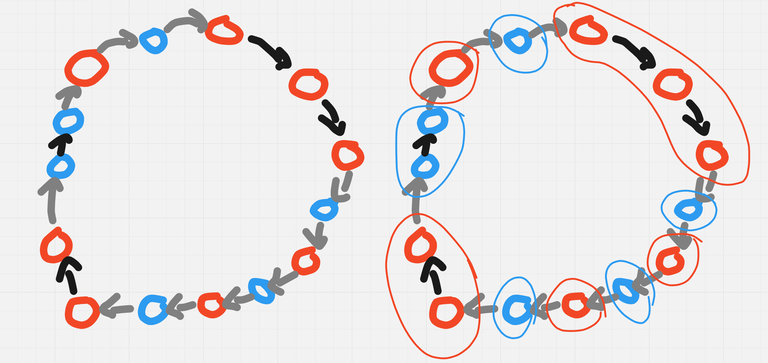

- Suppose the impostor is not in the cycle. Then observe that the only time you get an edge with weight $$$1$$$ is whenever there are two consecutive nodes with different roles. — Consider consecutive segments of nodes with the same role in this cycle, and compress each of this segments into one node. The image bellow illustrates how, grey edges are queries with answer no.

The new graph is bipartite, and thus has an even number of edges. But all the edges in this new graph, are all the grey edges in the original graph, which implies what we want.

If the impostor is in the cycle, there are three ways of inserting it (assume the cycle has more than $$$2$$$ nodes that case is exactly what we proved in hint 2).

- We can insert the impostor into one of this ``segments'' of consecutive nodes with the same role. This would increase the number of grey edges by $$$1$$$, changing the parity,

- We can insert it between two segments.

- If we have Knight $$$\mapsto$$$ Impostor $$$\mapsto$$$ Knave, the number of grey edges decreases by $$$1$$$.

- If thee is Knave $$$\mapsto$$$ Impostor $$$\mapsto$$$ Knight, the number of grey edges increases by $$$1$$$.

Either way, we changed the parity of the cycle. $$$\blacksquare$$$

The algorithm that solves the problem is the following:

If $$$n = 3$$$,

query $$$1 \mapsto 2$$$ and $$$2 \mapsto 1$$$,

If queries match, $$$3$$$ is the impostor.

Else, query $$$1 \mapsto 3$$$ and $$$3 \mapsto 1$$$.

- If queries match, $$$2$$$ is the impostor.

- Else, $$$1$$$ is the impostor.

Else, $$$n > 3$$$. To solve $$$n > 3$$$ players with $$$n$$$ queries, do:

While $$$n > 5$$$,

- query $$$n \mapsto n - 1$$$ and $$$n - 1 \mapsto n$$$.

- If their answers don't match, one of them is the impostor. Query $$$n \mapsto n - 2$$$ and $$$n - 2 \mapsto n$$$.

- If their answers don't match, $$$n$$$ is the impostor.

- Otherwise, $$$n - 1$$$ is the impostor.

- If the answers match, do $$$n -= 2$$$.

- If their answers don't match, one of them is the impostor. Query $$$n \mapsto n - 2$$$ and $$$n - 2 \mapsto n$$$.

- query $$$n \mapsto n - 1$$$ and $$$n - 1 \mapsto n$$$.

If $$$n > 5$$$ doesn't hold and we haven't found the impostor, we either have the $$$n = 4$$$ case or the $$$n = 5$$$ case, we solve them optimally in $$$4$$$ or $$$5$$$ queries each.

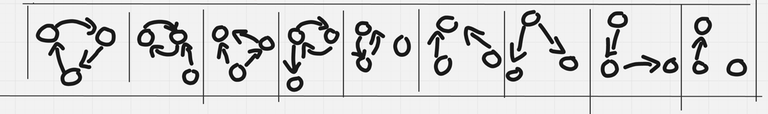

To solve $$$n = 5$$$ in $$$5$$$ queries,

We will form a cycle of size $$$3$$$, asking for $$$1 \mapsto 2$$$, $$$2 \mapsto 3$$$ and $$$3 \mapsto 2$$$ (blue edges in the image below).

- If the cycle has an even number of no's, we know the impostor is among $$$4$$$ or $$$5$$$. So we ask $$$3 \mapsto 4$$$ and $$$4 \mapsto 3$$$ (green edges).

- If both queries match, $$$5$$$ is the impostor.

- Else, $$$4$$$ is the impostor.

- Else, The impostor is among us (among the cycle, I mean). Ask $$$1 \mapsto 3$$$ and $$$2 \mapsto 1$$$ (purple edges).

- If $$$1 \mapsto 2$$$ doesn't match with $$$2 \mapsto 1$$$ and $$$1 \mapsto 3$$$ doesn't match with $$$3 \mapsto 1$$$, $$$1$$$ is the impostor.

- If $$$1 \mapsto 2$$$ doesn't match with $$$2 \mapsto 1$$$ and $$$1 \mapsto 3$$$ matches with $$$3 \mapsto 1$$$, $$$2$$$ is the impostor.

- If $$$1 \mapsto 2$$$ matches with $$$2 \mapsto 1$$$ and $$$1 \mapsto 3$$$ doesn't match with $$$3 \mapsto 1$$$, $$$3$$$ is the impostor.

- It is impossible for $$$1 \mapsto 2$$$ to match with $$$2 \mapsto 1$$$ and $$$1 \mapsto 3$$$ to match with $$$3 \mapsto 1$$$, because we know at least one of this cycles will contain the impostor.

To solve $$$n = 4$$$ in $$$4$$$ queries,

We will query $$$1 \mapsto 2$$$, $$$2 \mapsto 1$$$, $$$1 \mapsto 3$$$ and $$$3 \mapsto 1$$$.

- If $$$1 \mapsto 2$$$ doesn't match with $$$2 \mapsto 1$$$ and $$$1 \mapsto 3$$$ doesn't match with $$$3 \mapsto 1$$$, $$$1$$$ is the impostor.

- If $$$1 \mapsto 2$$$ doesn't match with $$$2 \mapsto 1$$$ and $$$1 \mapsto 3$$$ matches with $$$3 \mapsto 1$$$, $$$2$$$ is the impostor.

- If $$$1 \mapsto 2$$$ matches with $$$2 \mapsto 1$$$ and $$$1 \mapsto 3$$$ doesn't match with $$$3 \mapsto 1$$$, $$$3$$$ is the impostor.

- If $$$1 \mapsto 2$$$ matches with $$$2 \mapsto 1$$$ and $$$1 \mapsto 3$$$ matches with $$$3 \mapsto 1$$$, then $$$4$$$ is the impostor.

We have proven that that $$$f(n) \le \max(4, n)$$$. Now we will prove that $$$n \le f(n)$$$.

We will show it is impossible to solve the problem for any $$$n$$$ with only $$$n - 1$$$ queries. We will show that the grader always has a strategy of answering queries, such that there exists at least 2 different assignments of roles that are consistent with the answers given, and have different nodes as the impostor.

Consider the directed graph generated from the queries. By pigeonhole principle at least one node has in-degree $$$0$$$, and at least one node has out-degree $$$0$$$.

If those two nodes are different, call $$$A$$$ the node with in-degree $$$0$$$ and $$$B$$$ the node with out-degree $$$0$$$. Let the grader always reply yes to your queries.

- $$$A$$$ can be the impostor and everyone else Knaves.

- $$$B$$$ can be the impostor and everyone else Knights.

If those two nodes are the same, then the graph looks like a collection of cycles and one isolated node. The grader will always reply yes except for the last query where it replies no. Let the last query be to player $$$A$$$ about player $$$B$$$. The two assignments of roles are:

- $$$A$$$ is the impostor and everyone else in the cycle is a Knight.

- $$$B$$$ is the impostor and everyone else in the cycle is a Knave.

Thus, we have shown that regardless what the questions asked are, it is impossible to find the impostor among $$$n$$$ players, in $$$n - 1$$$ queries. $$$\blacksquare$$$

Now, we prove that $$$f(3) = 4$$$:

Stare at this image:

lol,

Actually, one of the testers coded the exhaustive checker. I will let them post their code if they want to.

#include <bits/stdc++.h>

using namespace std;

int n;

void answer (int a) {

cout << "! " << a << endl;

}

int query (int a, int b) {

cout << "? " << a << " " << b << endl;

int r;

cin >> r;

if (r == -1)

exit(0);

return r;

}

void main_ () {

cin >> n;

if (n == -1)

exit(0);

if (n == 3) {

if (query(1, 2) != query(2, 1)) {

if (query(1, 3) != query(3, 1)) {

answer(1);

} else {

answer(2);

}

} else {

answer(3);

}

return;

}

for (int i = 1; i + 1 <= n; i += 2) {

if (n % 2 == 1 && i == n - 4)

break;

if ((n % 2 == 0 && i + 1 == n) || query(i, i + 1) != query(i + 1, i)) {

int k = 1;

while (k == i || k == i + 1)

k++;

if (query(i, k) != query(k, i)) {

return answer(i);

} else {

return answer(i + 1);

}

}

}

vector<int> v = {

query(n - 4, n - 3),

query(n - 3, n - 2),

query(n - 2, n - 4)

};

if ((v[0] + v[1] + v[2]) % 2 == 0) {

if (query(n - 3, n - 4) != v[0]) {

if (query(n - 2, n - 3) != v[1]) {

answer(n - 3);

} else {

answer(n - 4);

}

} else {

answer(n - 2);

}

} else {

if (query(n, 1) != query(1, n)) {

answer(n);

} else {

answer(n - 1);

}

}

}

int main () {

int t;

cin >> t;

while (t--)

main_();

return 0;

}

In the Olympiad version, the impostor behaved differently. It could either disguise as a Knight while secretly being a Knave, or disguise as a Knave while secretly being a Knight. Turns out the test cases and the interactor in both versions are practically the same. Why would that be?

Do small cases! Let the pencil (or the computer) do the work and use your brain to look out for patterns.

Try to find the most natural and simple way of modeling the problem.

Learn how to code a decision tree, or other models to exhaustively search for constructions, proof patterns, recursive complete search, etc. and build intuition on that to solve the more general cases of the problem.

2022E1 - Billetes MX (Easy Version)

Consider the extremal cases, what is the answer if the grid is empty? What is the answer if the grid is full? What happens if $$$N = 2$$$?

Observe that if $$$N = 2$$$, the xor of every column is constant. Can we generalize this idea?

Imagine you have a valid full grid $$$a$$$. For each $$$i$$$, change $$$a[0][i]$$$ to $$$a[0][0]\oplus a[0][i]$$$. Observe that the grid still satisfies the condition!

Using the previous idea we can show that for any valid grid, there must exist two arrays $$$X$$$ and $$$Y$$$, such that $$$a[i][j] = X[i] \oplus Y[j]$$$.

Consider doing the operation described in hint 4 for every row and every column of a full grid that satisfies the condition;

- That is, for each row, and each column, fix the first element, and change every value in that row or column by their xor with the first element.

We will be left with a grid whose first row and first column are all zeros.

But this grid also satisfies the condition! So it must hold that $$$a[i][j] \oplus a[i][0] \oplus a[0][j] \oplus a[0][0] = 0$$$, but 3 of this values are zero!

We can conclude that $$$a[i][j]$$$ must also be zero. This shows that there must exist two arrays $$$X$$$ and $$$Y$$$, such that $$$a[i][j] = X[i] \oplus Y[j]$$$, for any valid full grid.

Think of each tile of the grid that we know of, as imposing a condition between two elements of arrays $$$X$$$ and $$$Y$$$. For each tile added, we lose one degree of freedom right? We could make a bunch of substitutions to determine new values of the grid. How can we best model the problem now?

Think about it as a graph where the nodes are rows and columns, and there is an edge between row $$$i$$$ and column $$$j$$$ with weight $$$a[i][j]$$$. Substitutions are now just paths on the graph. If we have a path between the node that represents row $$$i$$$ and column $$$j$$$, the xor of the weights in this path represents the value of $$$a[i][j]$$$. What happens if there's more than one path, and two paths have different values?

To continue hint 7, we can deduce that if there is a cycle with xor of weights distinct to $$$0$$$ in this graph, there would be a contradiction, and arrays $$$X$$$ and $$$Y$$$ can't exist. How can we check if this is the case?

Do a dfs on this graph, maintaining an array $$$p$$$, such that $$$p[u]$$$ is the xor of all edges in the path you took from the root, to node $$$u$$$. Whenever you encounter a back edge between nodes $$$u$$$ and $$$v$$$ with weight $$$w$$$, check if $$$p[u] \oplus p[v] = w$$$.

So lets assume there is no contradiction, ie, all cycles have xor 0. What would be the answer to the problem? We know that if the graph is connected, there exists a path between any two tiles and all the values of the tiles would be determined. So, in how many ways can we make a graph connected?

Say there are $$$K$$$ connected components. We can connect them all using $$$K - 1$$$ edges. For each edge, there are $$$2^{30}$$$ possible values they can have. Thus, the number of ways of making the graph connected is $$$\left(2^{30} \right)^{K - 1}$$$.

Why is this the answer to the problem?

This is just the solution. Please read the hints in order to understand why it works and how to derive it.

Precompute an array $$$c$$$, with $$$c[i] = 2^{30\cdot i} \pmod{10^9 + 7}$$$.

Let $$$a$$$ be the 2d array with known values of the grid. Consider the graph formed by adding an edge between node $$$i$$$ and node $$$j + n$$$ and weight $$$a[i][j]$$$ for every known tile $$$(i, j)$$$ in the grid. Iterate from $$$1$$$ to $$$n + m$$$ maintaining an array $$$p$$$ initialized in $$$-1$$$s. If the current proceed node hasn't been visited, we run a dfs through it. We will use array $$$p$$$ to maintain the running xor for each node during the dfs. If we ever encounter a back edge between nodes $$$u, v$$$ and weight $$$w$$$, we check if $$$p[u] \oplus p[v] = w$$$. If not, we the answer is zero. If this condition always holds, let $$$K$$$ be the number of times you had to run the dfs. $$$K$$$ is also the number of connected components in the graph. The answer is $$$c[K - 1]$$$.

Complexity: $$$\mathcal{O}(n + m + k)$$$.

#include <bits/stdc++.h>

using namespace std;

int const Mxn = 2e5 + 2;

long long int const MOD = 1e9 + 7;

long long int precalc[Mxn];

vector<vector<array<int, 2>>> adj;

bool valid = 1;

int pref[Mxn];

void dfs(int node) {

for (auto [child, w] : adj[node]) {

if (pref[child] == -1) {

pref[child] = pref[node]^w;

dfs(child);

} else {

if ((pref[child]^pref[node]) != w) valid = 0;

}

}

}

int main() {

precalc[0] = 1;

for (int i = 1; i < Mxn; i++) {

precalc[i] = (precalc[i - 1]<<30)%MOD;

}

int tt;

for (cin >> tt; tt; --tt) {

int N, M, K, Q;

cin >> N >> M >> K >> Q;

adj.clear();

adj.assign(N + M, vector<array<int, 2>>{});

int x, y, z;

for (int i = 0; i < K; i++) {

cin >> x >> y >> z;

x--, y--;

adj[x].push_back({y + N, z});

adj[y + N].push_back({x, z});

}

for (int i = 0; i < N + M; i++) pref[i] = -1;

valid = 1;

int cnt = 0;

for (int i = 0; i < N + M; i++) {

if (pref[i] != -1) continue;

cnt++; pref[i] = 0; dfs(i);

}

if (valid) cout << precalc[cnt - 1] << '\n';

else cout << 0 << '\n';

}

}

2022E2 - Billetes MX (Hard Version)

Please read the solution to E1 beforehand, as well as all the hints.

Through the observations in E1, we can reduce the problem to the following: We have a graph, we add edges, and we want to determine after each addition if all its cycles have xor 0, and the number of connected components in the graph.

The edges are never removed, so whenever an edge is added that creates a cycle with xor distinct to zero, this cycle will stay in the graph for all following updates. So we can binary search the first addition that creates a cycle with xor distinct to zero, using the same dfs we used in E1. After the first such edge, the answer will always be zero.

Now, for all the additions before that, we must determine how many connected components the graph has at each step. But this is easily solvable with Disjoint Set Union.

Complexity: $$$\mathcal{O}(\log(q)(n + m + k + q) + \alpha(n + m)(q + k))$$$.

We will answer the queries online. Remember that if the graph only contains cycles with xor $$$0$$$, the xor of a path between a pair of nodes is unique. We'll use this in our advantage. Let $$$W(u, v)$$$ be the unique value of the xor of a path between nodes $$$u$$$ and $$$v$$$.

Lets modify a dsu, drop the path compression, and define array $$$p$$$, that maintains the following invariant:

For every node $$$u$$$ in a component with root $$$r$$$, $$$W(u, r)$$$ equals the xor of $$$p[x]$$$ for all ancestors $$$x$$$ of $$$u$$$ in our dsu (we also consider $$$u$$$ an ancestor of itself).

Whenever we add an edge between two nodes $$$u$$$ and $$$v$$$ in two different components with weight $$$w$$$, we consider consider the roots $$$U$$$ and $$$V$$$ of their respective components. Without loss of generality, assume $$$U$$$'s component has more elements than $$$V$$$'s. We will add an edge with weight $$$W(u, U) \oplus W(v, V) \oplus w$$$ between $$$V$$$ and $$$U$$$, and make $$$U$$$ the root of our new component.

This last step is the small to large optimization, to ensure the height of our trees is logarithmic.

With this data structure, we can maintain the number of connected components like in a usual dsu, and whenever an edge $$$(u, v)$$$ with weight $$$w$$$ is added, and $$$u$$$ and $$$v$$$ belong to the same component, we can obtain the value of $$$W(u, v)$$$ in $$$\mathcal{O(\log(n))}$$$, and check if it is equal to $$$w$$$.

This idea is similar to the data structure described here, and is useful in other contexts.

Complexity: $$$\mathcal{O}(\log(q + k)(n + m + k + q))$$$.

#include <bits/stdc++.h>

using namespace std;

int const Mxn = 2e5 + 2;

long long int const MOD = 1e9 + 7;

vector<vector<array<int, 2>>> adj;

vector<array<int, 3>> Edges;

long long int precalc[Mxn];

struct DSU {

vector<int> leader;

vector<int> sz;

int components;

DSU(int N) {

leader.resize(N); iota(leader.begin(), leader.end(), 0);

sz.assign(N, 1);

components = N;

}

int find(int x) {

return (leader[x] == x) ? x : (leader[x] = find(leader[x]));

}

void unite(int x, int y) {

x = find(x), y = find(y);

if (x == y) return;

if (sz[x] < sz[y]) swap(x, y);

leader[y] = leader[x]; sz[x] += sz[y];

components--;

}

};

bool valid = 1;

int pref[Mxn];

void dfs(int node = 0) {

for (auto [child, w] : adj[node]) {

if (pref[child] == -1) {

pref[child] = pref[node]^w;

dfs(child);

} else {

if ((pref[child]^pref[node]) != w) valid = 0;

}

}

}

int main() {

precalc[0] = 1;

for (int i = 1; i < Mxn; i++) {

precalc[i] = (precalc[i - 1]<<30)%MOD;

}

int tt;

for (cin >> tt; tt; --tt) {

int N, M, K, Q;

cin >> N >> M >> K >> Q;

Edges.clear();

adj.clear();

adj.assign(N + M, vector<array<int, 2>>{});

DSU dsu(N + M);

dsu.components = N + M;

int x, y, z;

for (int i = 0; i < K; i++) {

cin >> x >> y >> z;

x--, y--;

adj[x].push_back({y + N, z});

adj[y + N].push_back({x, z});

dsu.unite(x, y + N);

}

for (int i = 0; i < Q; i++) {

cin >> x >> y >> z;

x--, y--;

Edges.push_back({x, y + N, z});

}

int firstzero = 0;

for (int k = 20; k >= 0; k--) {

if (firstzero + (1<<k) > Q) continue;

for (int i = firstzero; i < firstzero + (1<<k); i++) {

x = Edges[i][0], y = Edges[i][1], z = Edges[i][2];

adj[x].push_back({y, z});

adj[y].push_back({x, z});

}

valid = 1;

for (int i = 0; i < N + M; i++) pref[i] = -1;

for (int i = 0; i < N + M; i++) {

if (pref[i] == -1) pref[i] = 0, dfs(i);

}

if (!valid) {

for (int i = firstzero + (1<<k) - 1; i >= firstzero; --i) {

x = Edges[i][0], y = Edges[i][1];

adj[x].pop_back();

adj[y].pop_back();

}

} else {

firstzero += (1<<k);

}

}

if (firstzero == 0) {

valid = 1;

for (int i = 0; i < N + M; i++) pref[i] = -1;

for (int i = 0; i < N + M; i++) {

if (pref[i] == -1) pref[i] = 0, dfs(i);

}

if (!valid) firstzero--;

}

for (int i = 0; i <= Q; i++) {

if (i <= firstzero) cout << precalc[dsu.components - 1] << '\n';

else cout << 0 << '\n';

if (i == Q) break;

x = Edges[i][0], y = Edges[i][1];

dsu.unite(x, y);

}

}

}

In our Olympiad, we had $$$v_i \le 1$$$ instead of $$$v_i \le 2^{30}$$$, and we also had a final subtask were tiles could change values. How would you solve this?

We have three different solutions for this problem, one of them found during the Olympiad! I'll let the contestant who found it post it if he wants to.

You can model a grid as a bipartite graph between rows and columns.

Whenever coding or designing a data structure, keep in mind all the invariants you are maintaining. I like to think of data structures as graphs with invariants or monovariants in each node. I have a blog draft on how to use this to design data structures, inspired by this. Maybe I will publish it.